Non-profit to grade transparency in government policymaking

The non-profit Evidence for Democracy has released a framework to judge government policies based on the level of transparency around scientific evidence.

The organization plans to release a systematic assessment of the level of transparency in government departments this fall, according to Rachael Maxwell, the executive director of Evidence for Democracy. The approach they’ve developed has been used to grade only a set of sample policies so far.

Maxwell said the framework is designed to judge how well the public can follow the “chain of reasoning” for decisions the government has made.

"The crux of this work is asking, ‘can someone from outside government tell what the government is proposing to do, why, and on what basis?’” she said in an interview with Research Money.

“It is not about judging the quality of evidence used for government policy, it is about the evidence being available for the public to view and understand.”

Evidence for Democracy’s framework draws from an approach developed by the UK non-profit Sense about Science. It judges policies on transparency in four categories (descriptions in parentheses ours):

- Diagnosis (what policymakers know about the issue)

- Proposal (the government's chosen intervention)

- Implementation (how it will be rolled out)

- Testing and Evaluation (how we know it worked)

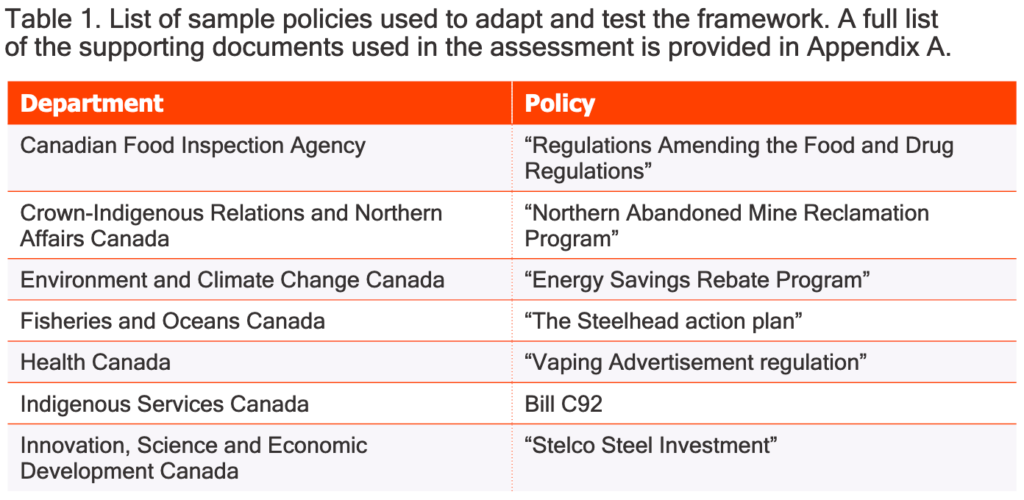

A set of policies was chosen to test whether Sense about Science’s framework could be applied to a Canadian context. Each policy was rated from 0 to 3 in each of the categories.

Of the seven sample policies chosen, five scored poorly on their level of transparency — no category received above a 1 — but two policies related in Indigenous issues, Bill C92 and the Northern Abandoned Mine Reclamation Program, scored higher.

Maxwell said it’s possible that the civil servants provide more evidence to bolster their government’s case for controversial issues like Crown-Indigenous relations, but any conclusions have to wait until they are able to conduct a more thorough assessment.

[caption id="attachment_24594" align="alignnone" width="640"] Most of the seven sample policies scored poorly under Evidence for Democracy's transparency framework. To score a "1," evidence must be mentioned with an explanation for how it is used. (Evidence for Democracy)[/caption]

Most of the seven sample policies scored poorly under Evidence for Democracy's transparency framework. To score a "1," evidence must be mentioned with an explanation for how it is used. (Evidence for Democracy)[/caption]

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis, there's been more demand for clarity on why exactly a decision is being made and what the evidence is to support it, Maxwell says.

"Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, I don't think the temperature on government transparency was hot,” she said. "It was easy to look at it as a ‘nice-to-have’ in policy-making — something to do when time and resources permitted."

“In the last fifteen months, the appetite for evidence and for understanding the basis of the decisions that have significantly and deeply impacted people's lives — their families, their businesses, their livelihoods — have shifted dramatically.”

Accountability improved under Harper and Trudeau governments

Research Money previously spoke to Maxwell about evidence-based decision-making and her plans for Evidence for Democracy as their new executive director. The organization was founded during the administration of Prime Minister Stephen Harper to oppose cuts to scientific research programs and the muzzling of federal scientists.

Despite their opposition to Harper’s science policies, Maxwell gives his administration credit for accountability measures such as the Federal Accountability Act, which led to the creation of the Conflict of Interest and Ethics Commissioner, the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner and the Commission of Lobbying.

The Trudeau administration has since made more moves to increase transparency and incorporate scientific advice into policy-making, such as making ministerial mandate letters open to the public and creating the Office of the Chief Science Advisor.

However, Maxwell says the Liberal government’s commitment to evidence-based decision-making is impossible to evaluate without transparency. She hopes that publishing assessments on their policies will push the government to communicate better, she said.

In the past, she said, “governments have assumed that the public just isn't interested in that level of information.”

R$

| Organizations: | |

| People: | |

| Topics: |

Events For Leaders in

Science, Tech, Innovation, and Policy

Discuss and learn from those in the know at our virtual and in-person events.

See Upcoming Events

You have 0 free articles remaining.

Don't miss out - start your free trial today.

Start your FREE trial Already a member? Log in

By using this website, you agree to our use of cookies. We use cookies to provide you with a great experience and to help our website run effectively in accordance with our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.