Age no barrier to entrepreneurship in Canada

With Chad Saunders

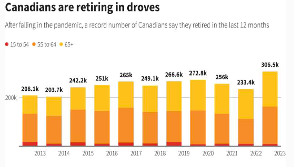

While Canada mostly avoided the Great Resignation experienced in other jurisdictions, we are in the midst of a Great Retirement, which is leading to staff shortages across many industries. This is in spite of levels of employment engagement that are returning to pre-pandemic levels1. Will we need to entice these retirees back into the labour force and is entrepreneurship a way to do it?

Statistics Canada defines retirement as, “…a person who is aged 55 and over, who is not in the labour force and receives 50 percent or more of his or her total income from retirement-like sources, such as the Canada Pension Plan and Old Age Security.”2

There are 7.3 million Canadians aged 65 and older, or about 18 percent of the population, most of whom are no longer working. This group is projected to grow to 12 million by 2051, when they will represent about 25 percent of the population.

In addition, in 2021 almost a million people aged 55-64 were no longer working2. These older adults are healthier, richer, and more educated than previous generations. By the time they reach 65, on average, they can expect to live another 21 years.

What this growing cohort does in their “retirement”, therefore, will have a major effect on the Canadian economy.

A report2 from Statistics Canada reveals more about older adults’ activities:

- In 2015, one in five Canadians aged 65 and older, or nearly 1.1 million seniors, reported working during the year. This is the highest proportion recorded since the 1981 Census.

- Of the seniors who worked in 2015, about 30 percent did so year round, full time, with the majority of them being men.

- The percentage of seniors who reported working nearly doubled between 1995 and 2015, with most of the increase coming from part‑year or part‑time work. Increases in work activity were observed at all ages, for men and women alike.

- Seniors with a bachelor’s degree or higher, and those without private retirement income were more likely to work than other seniors.

- Employment income was the main source of income for 43.8 percent of seniors who worked in 2015, up from 40.4 percent in 2005 and 38.8 percent in 1995.

- Common occupations for senior men working year round, full time: managers in agriculture; retail and wholesale trade managers; transport truck drivers; retail salespersons; and janitors, caretakers and building superintendents.

- Common occupations for senior women working year round, full time: administrative assistants; managers in agriculture; administrative officers; retail salespersons; general office support workers; and retail and wholesale trade managers.

- Seniors in the territories, as well as in Saskatchewan, Alberta and Prince Edward Island were the most likely to work. Those in Newfoundland and Labrador, Quebec, and New Brunswick were the least likely to do so.

- Across the country, seniors living in rural areas were more likely to work than seniors living elsewhere.

Unfortunately, older adults do not show up in most policy reports on entrepreneurship and one wonders why? One explanation is that the data is not collected since it is assumed that after age 65, individuals are retired and no longer active in the labour force. That has been the assumption for the world’s largest study of entrepreneurship, conducted by the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) annually in over 70 countries. However, GEM Canada is the exception, and data has been collected on Canadian entrepreneurs aged 18-79.

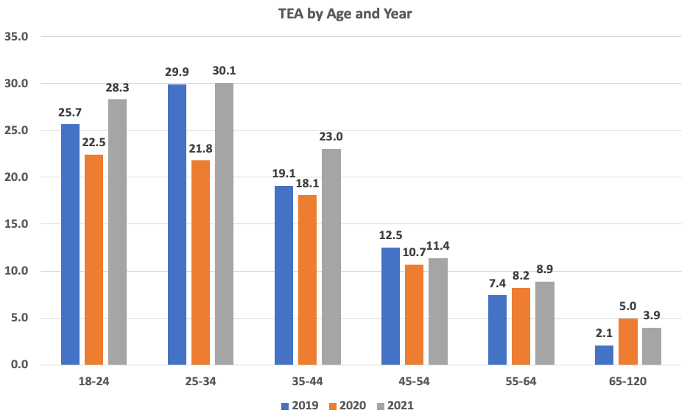

The table below shows the trends in entrepreneurial levels by age group in Canada from 2019-2021, based upon the Canadian GEM data3.

[caption id="attachment_30039" align="aligncenter" width="690"] Source: GEM Canada data 2019-2021[/caption]

Source: GEM Canada data 2019-2021[/caption]

The vertical axis is the Total Early-stage Activity (TEA) rate, the percentage of the adult population planning a new venture, plus those operating one less than 42 months old.

Entrepreneurship rates among those older than 55 are lower than those aged 25-34, the peak age to start a company in Canada. However, compared with many other countries, these are very high levels. For example, in Poland the TEA rate in 2021 for the 18-64 age group was 2.0, in Italy 4.8 and Japan 6.3. By international standards, then, older Canadians are very entrepreneurial.

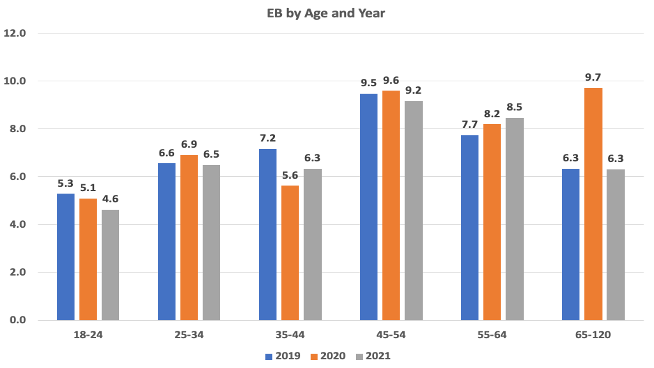

Another entrepreneurial activity older adults engage in is owning and managing an existing company. The graph below shows the trend in the rate of owner managers by age from 2019 to 2021.

[caption id="attachment_30040" align="aligncenter" width="654"] Source: GEM Canada data 2019-2021[/caption]

Source: GEM Canada data 2019-2021[/caption]

As you might expect, this shows a very different pattern to the startups, as older adults own businesses at a much higher rate than younger adults. Older adults have had more time to build up their businesses and make them sustainable in the long term.

Conclusion

There is a lot of evidence4 that working past the traditional retirement age of 65 is beneficial to mental and physical health. Being an entrepreneur is a significant part of this. Having a focus on encouraging older adults to become entrepreneurs should be an important part of a program to engage older adults in economic activity. This would have many benefits for both the individuals involved and the economy as a whole.

This article was co-authored with Chad Saunders, Associate Professor at the Haskayne School of Business at the University of Calgary. Peter Josty is Executive Director of The Centre for Innovation Studies (THECIS), a Calgary-based not-for-profit research company specializing in innovation and entrepreneurship. In addition to working in private research and business development, he holds a PhD in chemistry from the University of London and an MBA from the International Institute for Management Development in Geneva.Chad Saunders

- Gordon, Julie (2022). Canada’s real problem is not job losses, it’s the rush to retire. Reuters Business News, Sept 12, 2022.

- Statistics Canada (2017). Census in Brief: Working Seniors in Canada, https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/as-sa/98-200-x/2016027/98-200-x2016027-eng.cfm

- Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Canada data 2019, 2020 and 2021.

- Baxter, S., Blank, L., Cantrell, A., Goyder, E. (2021). Is working in later life good for your health? A systematic review of health outcomes resulting from extended working lives. BMC Public Health. 21, 1356. https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-021-11423-2

| Organizations: | |

| People: | |

| Topics: |

Events For Leaders in

Science, Tech, Innovation, and Policy

Discuss and learn from those in the know at our virtual and in-person events.

See Upcoming Events

You have 0 free articles remaining.

Don't miss out - start your free trial today.

Start your FREE trial Already a member? Log in

By using this website, you agree to our use of cookies. We use cookies to provide you with a great experience and to help our website run effectively in accordance with our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.